Darlene Keju's groundbreaking 1983 address to the World Council of Churches in Vancouver, Canada.

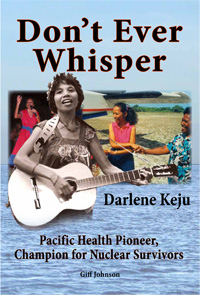

BOOK REVIEW: DON'T EVER WHISPER:

Darlene Keju: Pacific health pioneer, champion for nuclear survivors

By Giff Johnson, 2013.

USA, Charleston, SC: Book link.

By Celine Kearney for the Pacific Media Centre

Don’t Ever Whisper is Giff Johnson’s biography of his wife Darlene Keju-Johnson, a Marshallese woman who reached out to a global audience about the health effects of US nuclear tests on her people, including cancers and birth deformities. At the same time, the book documents Marshallese politics and the duplicity of US administrations that allowed the Marshall Islands and the people to be used for nuclear tests in the 1940s and 1950s, conducting studies out of sight of mainstream media.

US government policy was that Bikini, Enewetak, Rongelap and Utrick were the only radiation affected atolls, but this deliberately covered up fallout dangers.

Don’t Ever Whisper is also a case study of how a fiercely committed, energetic and optimistic young woman developed a group of youth health workers, Youth to Youth in Health (YTYIH), part of the Ministry of Health’s health promotion programme, working as peer educators on inner and outer islands.

The philosophy of health promotion that Darlene developed with her team was multifaceted. It nurtured traditional Marshallese culture and later income generation through traditional crafts and growing and harvesting food, to create sustainable livelihoods.

Darlene’s salary was paid by the government but the work of YTYIH was funded by a number of overseas agencies, while she networked with communities, organisations and businesses.

Darlene Keju was born in 1951, on Wotje atoll, the third of 11 children. By then, seven of the 67 nuclear tests conducted by the US at Bikini and Enewetak atolls between 1946 and 1958, had already been exploded. She died of cancer two months after her 45th birthday.

Giff draws on Darlene’s diaries, a wide range of letters, interviews, official documents, as well newspaper and broadcast reports. He also uses his own long experience of working to make public information about Micronesia and the effects of US testing there.

Radiation treatment

Among all this, Giff Johnson, a journalist, editor of the Marshall Islands Journal and a resident in the country since the mid-1980s, weaves vignettes of their life together, their respective families and friends, their journey around outer islands talking to people documenting effects of nuclear tests, their marriage in 1982, and their sustained work to gather and share information about the Marshallese people and others affected by the tests.

Darlene herself received three programmes of radiation treatment over 4 to 5 years, preferring to use traditional Marshallese medicines and treatments, which would allow her to continue to work with YTYIH.

Darlene is buried in a family cemetery on a small bluff in a rural area of Majuro. The words “Tuak Bwe Elimajnono”, “Face your challenges,” are on her grave stone.

Giff writes: “Darlene’s message to us, clear in life as it was in death: Don’t be afraid to make your way through strong ocean currents to get to the next island” (p. 365).

She made her own way through the strong currents of life, supported by parents who “were not afraid to speak their minds” and many friends. She went to school on Ebeye Island on Kwajalein Atoll, and at 16 was sent by her father to Hawai’i for further education. She faced the challenges of learning English, and living in a different culture, graduating with a Masters in Public Health from the University of Hawai’i, the first Marshallese woman with a higher public health degree.

She returned home in 1984 after 11 years in Hawai’i, to work to support the health needs of the Marshallese people. “A risk taker with a purpose,” she overcame “subtle but tangible” cultural, religious and government barriers in her community development work. (p. 9)

Giff observes that, through learning about her own people’s history, and the relationship with the United States, working with community leaders active in Hawaiian and Pacific anti-nuclear, land and sovereignty struggles, Darlene learned over time to appreciate the richness of her own culture and history.

Youth the key

She understood that Marshallese culture was being lost through Westernisation, and that working with the youth was key to sustaining it.

The book title Don’t Ever Whisper comes from a young woman trained as a peer educator. Invited by Darlene to say grace, it took prompting and three attempts till this shy young woman spoke loudly and clearly enough.

She recalls Darlene told the whole group “You have to let us hear your voice, your needs and your ideas. Don’t ever whisper. If I can’t hear it, nobody else will” (p. 264).

Darlene was astounded that a proper epidemiological study of the health of Marshall Islanders and the effects of nuclear testing had never been carried out. She had worked to plan one, though had not succeeded in having it conducted.

Her mother and father both had surgery for cancer. Her father died of cancer at 75. Her sister had died after complications of pregnancy, and it was the death of her older sister, Giff says, that “offers a clue as to why she developed into a fierce advocate for justice and change in the Marshall Islands” (p. 46).

In her health promotion work she networked with non government organisations, scientists, doctors and other health professionals who were challenging US governments’ negligence in radiation protection. She confronted powerful male professionals and politicians in the process.

Using instruments and voice, singing and serenade, she involved family and friends and health professionals, creating high energy and happiness, reaching out to youth and elders to promote community wellness One health professional described Darlene as a “female Pied Piper” “who led us all in reaching across language, education and financial divides to become friends” (p. 85).

In a nation where it was often considered inappropriate to communicate a problem or criticism directly, Darlene used drama as a vehicle for very straightforward messages such as the need for family planning. She invited Daniel Klein from Hawaii who worked in drama education for youth, to work with the YTYIH team.

Hope and courage

In his dedication, Giff quotes from a play Dan wrote in 1996: And the People Spoke Music: Stories of the Marshall Islands, about Letao, a mythical trickster hero, that “mirrored Darlene’s role in the Marshalls”.

Jiaban: ….You see what happens when you forget who you are? We need the bwebwenato, the old stories. We need them to fill us full of life and laughter, so we stay together and celebrate who we are.Giff’s book holds stories of Darlene’s energy, skills and formidable wisdom, as she inspired young people and their communities, offering hope and courage. She led the youth programme for 12 years. It eventually had 15 full time paid staff and is still running in 2013, 17 years after her death.

Lang: I don’t care about the stories.

Jiaban: Then our children are dead to us.

Our own New Zealand military service people were stationed in the mid-1970s on frigates at Moruroa and Fangatafa atolls to witness and oppose French nuclear testing. Given that they are currently challenging the government for compensation for ongoing illnesses and many deaths, we can learn from Giff ‘s story and Darlene’s life here in New Zealand.

Celine Kearney is New Zealand president of Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), an international women’s NGO affiliated to the United Nations. She is currently completing her PhD exploring the use of narrative in the construction of culture.

No comments:

Post a Comment